A Map of the Rhizome

If you know me, you know that I talk about rhizomes a lot. If you work with me, you know that I talk about rhizomes a lot. It might seem like I use the word rhizome to describe pretty much everything. Brains are rhizomes. Books are rhizomes. Societies are rhizomes. I often describe Nomic as a manufacturer of fine rhizomatic instruments. Nomic's pitchbook profile seems to agree:

"Developer of an information cartography platform intended to create fine rhizomatic instruments"

- Pitchbook on Nomic (2023)

Unfortunately, I don't think whoever wrote our pitchbook profile has any idea what a rhizome is. I fear that most people who hear or read the word rhizome don't know either. This post will attempt to clear up the confusion by describing what we talk about when we talk about rhizomes.

Etymology & Definition

The word rhizome comes from the Greek prefix rhiza-, meaning root, and the suffix -oma, meaning process or action. It is also worth noting that the Greek suffix -some, meaning body, is near cognate of -oma. A rough etymological definition of rhizome would therefore gesture at a rooting process or a rooted body. This tracks with the modern botanical sense of the word rhizome, which describes a horizontally growing mass of roots that can produce new shoots of a plant.

The philosophical sense of the word rhizome is a product of the ideas outlined in Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari's post-structuralist magnum opus A Thousand Plateaus (ATP). Unfortunately, ATP is written in the style of French 1980s intellectual discourse, and is not regarded for its clarity of presentation or its analytical precision. Equations like "Rhizomatics = Schizoanalysis = Stratoanalysis = Pragmatics = Micropolitics" (ATP 22) are both common and approximately useless for determining what rhizome actually means.

With this in mind, it is not surprising that ATP offers a 6 part "enumeration of certain approximate characteristics" when defining the rhizome. As such, I'm not going to start directly from the approximate definition of rhizome presented in the text. Instead, I'll build up the definition piece by piece through examples from rhizomes I have encountered in my life.

Connection & Heterogenety

Connectomics

One of my first encounters with a rhizome (though I didn't know what to call it yet) was in January of 2016. I was a freshman at Johns Hopkins University broadly interested in brain-computer interfaces, and I had signed up for an intersession course titled Introduction to Connectomics. In the course, I would learn that Connectomics was the science of producing and studying wiring diagrams of organisms' nervous systems. The promise of connectomics was that, by understanding what parts of an organism's brain connected to each other, we could learn something fundamental about how that organism behaved.

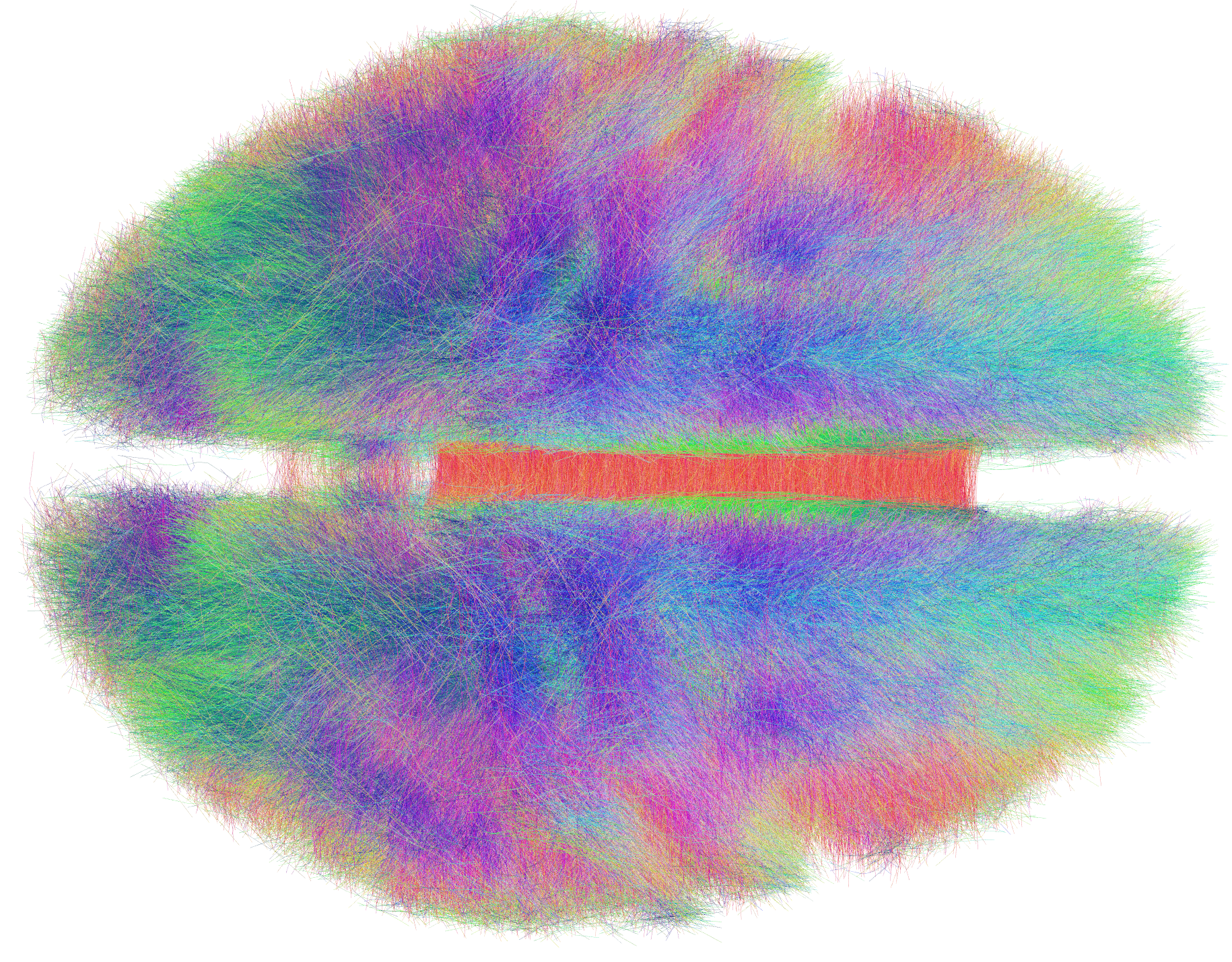

An estimated structural connectome of the human default mode network.

An estimated structural connectome of the human default mode network.

The above image of a connectome shares perceptual similarities with a tangled mass of roots. It has no clear entry or exit point. It is challenging to determine where one line ends and another beings. There is certainly structure, but it is not obvious what exactly that structure is or how it can be utilized. Yet, neuroscientists are able to harness connectomes to predict all kinds of physical phenomena, from the behavior of brain disease to the onset of schizophrenia.

I would learn that the neuroscientists' secret to taming the connectome was to view it through the lens of graph theory.

Graph Theory

Graph theory is the study of relations between objects. Using the language of graph theory, we call the relations being studied "edges", and the objects being studied "vertices." In the case of connectomics, graph theory is applied to model the connections (edges) between brain regions (vertices).

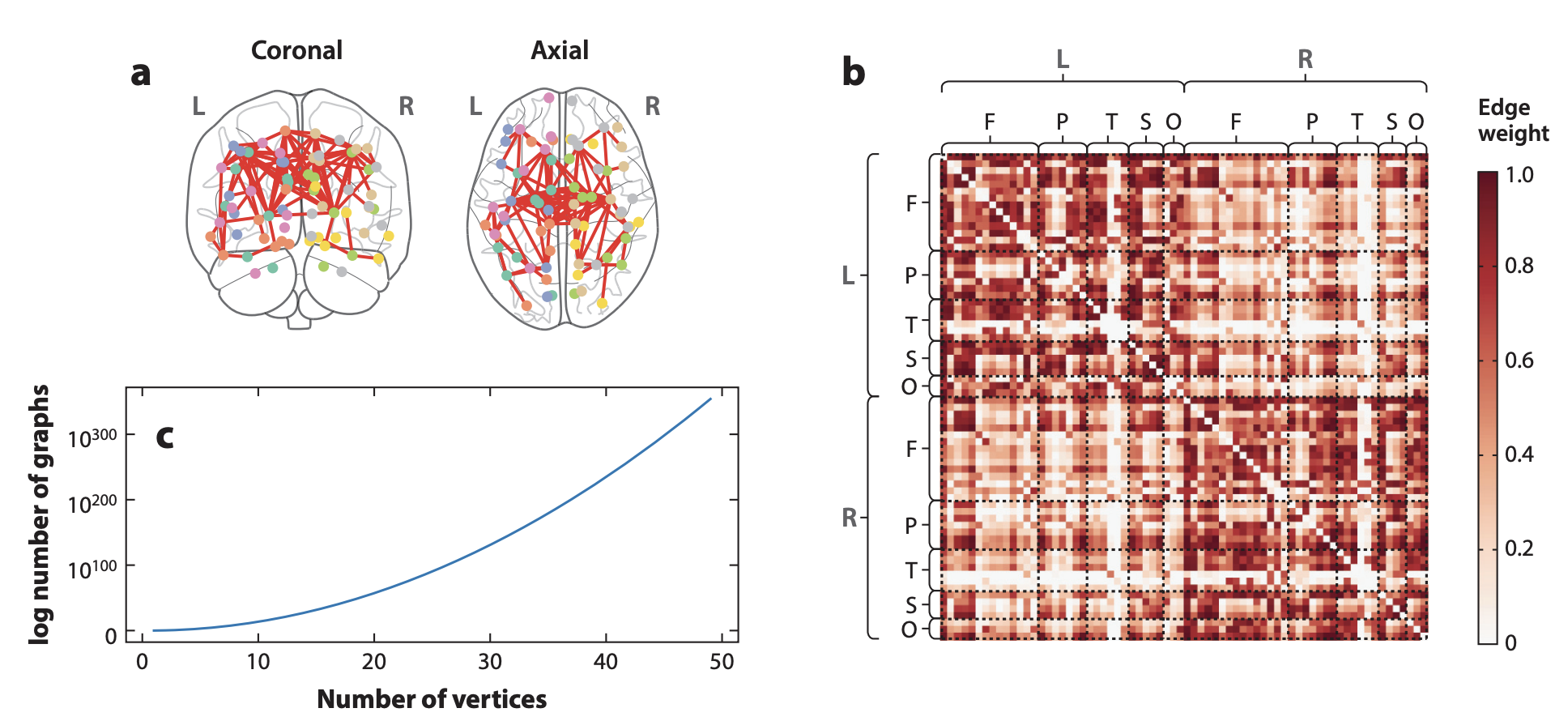

A figure from statistical connectomics depicting brains as graphs

A figure from statistical connectomics depicting brains as graphs

In panel A of the figure above, we see a stripped down depiction of a human connectome. Brain regions are identified with dots, and connections between brain regions are identified with lines. Panel B shows the adjacency matrix corresponding to the graph in panel A. The adjacency matrix encodes the edge weight (connection strength) between every pair of vertices (brain regions). The adjacency matrix also provides us with our first direct correlate to a principle of the rhizome:

Principle of Connection: Any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be

It is tempting at first to interpret the connectome-rhizome as restricted to the brain. The "points" are brain regions, and the collection of all their pairwise connections makes them rhizomatic. This interpretation is valid, but does not capture the full breadth that a rhizome is capable of achieving. A more complete picture of the connectome-rhizome encompasses both the connections between brain regions and the impact of brain structure on behavior.

In general, rhizomes have a tendency to transcend their apparent connective structure. The connectome is rhizomatic because it forms connections both within the anatomical domain as well as between the anatomical and behavioral domains. As Deleuze and Guattari put it:

Principle of Heterogenety: A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles. A semiotic chain is like a tuber agglomerating very diverse acts, not only linguistic, but also perceptive, mimetic, gestural, and cognitive.

Multiplicity

Introduction to Connectomics intrigued me enough that I began working with the network of professors involved in connectomics research at Hopkins. Through this research, I became increasingly familiar with the language of graph theory, and the range of applications that it could be applied in. This language proved to yield countless parallels to the ideas presented in ATP. One of these parallels is the relationship between the rhizome's principle of multiplicity and the graph theoretic idea of a link function. As an analogy:

adjacency matrix : connection :: link function : multiplicity

The Link Function

To understand the role of the link function, we first need to acquaint ourselves with the basics of the language of graph theory. We define a graph as a collection of vertices and edges :

In the case of a connectome, is the set of brain regions and is the set of pairwise connection strengths. A graph is often represented as an adjacency matrix . Each cell of the matrix contains the link function between the ith and jth vertex:

The link function is interpreted as the way in which we measure the strength of the connection between two vertices in our graph. One of the simplest link functions, the linear link function, associates each vertex with a d-dimensional vector, and considers their connection strength to be the dot product of their vectors. This link function leads to a very concise definition of the adjacency matrix . Let be the matrix of vectors associated with a vertex set. We have:

Keep that in mind. We will see it again later.

Multiplicity in the Wild

The world of link functions extends far beyond the linear link function. Connectomics makes use of a wide variety of link functions, including correlating bran region activity using fMRI and tracing neuron bundles using dMRI. In an information science paper recently brought to my attention by Paige Lee, social scientists use the link function of symbolic transfer entropy to quantify information flow between geographies on social media.

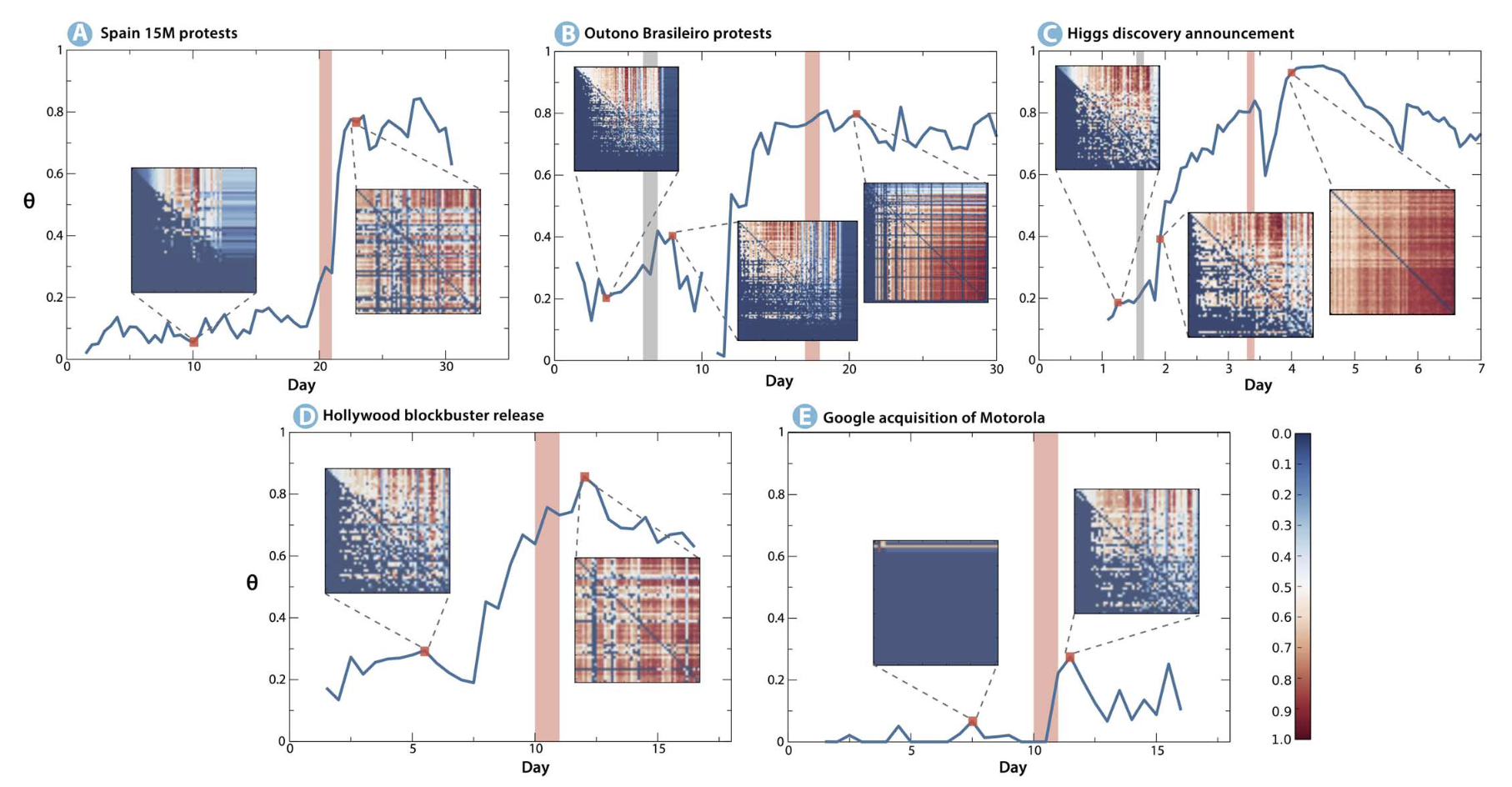

Adjacency matrices depicting geographic information flow before and after periods of coordinated social activity. During peace time, the information flows in one direction, as evidenced by the highly asymmetric adjacency matrices. During periods of unrest, the established hierarchy of information flow is upset, and information flows freely between all parts of the system.

Adjacency matrices depicting geographic information flow before and after periods of coordinated social activity. During peace time, the information flows in one direction, as evidenced by the highly asymmetric adjacency matrices. During periods of unrest, the established hierarchy of information flow is upset, and information flows freely between all parts of the system.

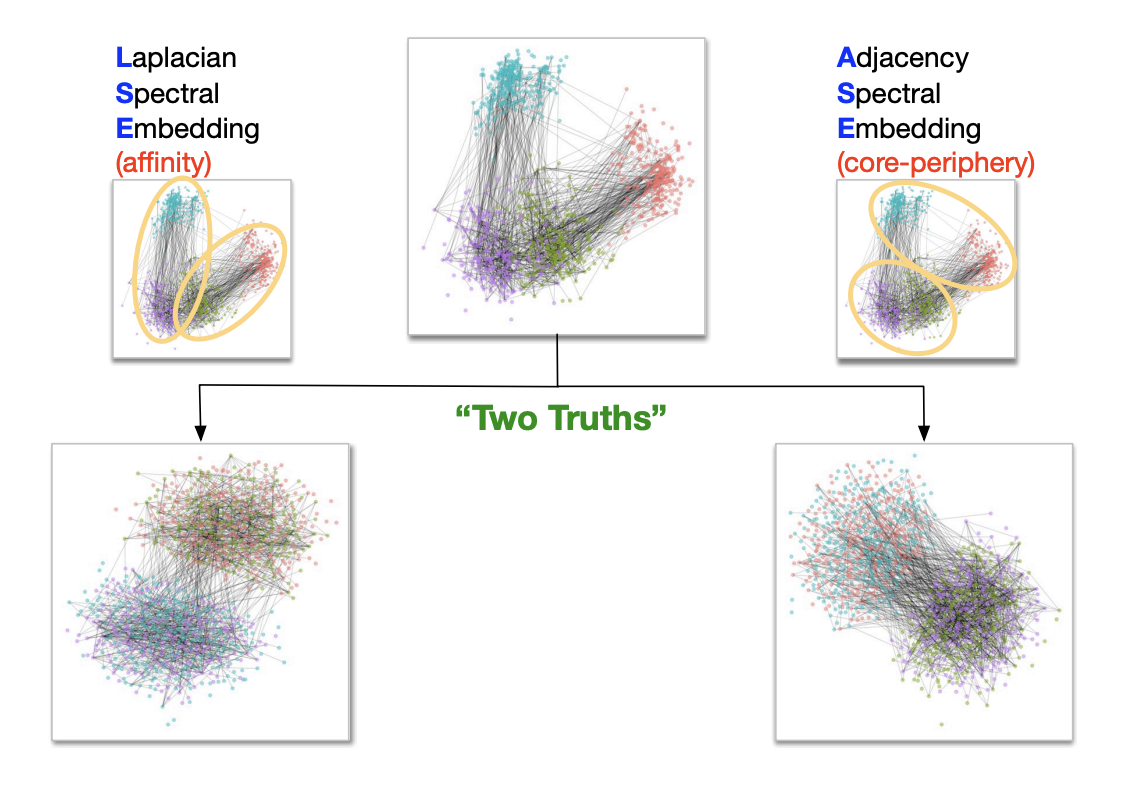

The choice of link function dramatically affects what properties are expressed in the resulting graph. One such example in the context of connectomics is the two truths paper. In the two truths paper, the same connectome is modeled as a graph using two different link functions. Using one of the link functions results in a graph that clusters by grey versus white matter, while using the other results in a graph that clusters by left versus right brain. Both distinctions have anatomical correlates, so neither is wrong - the choice of link function simply changes which distinction is expressed.

An illustration of the two truths phenomenon.

An illustration of the two truths phenomenon.

The two truths phenomenon demonstrates that we must take into account multiple ways of understanding what connection means. ATP codifies this as an aspect of the rhizome with the principle of multiplicity:

Principle of multiplicity: it is only when the multiple is effectively treated as a substantive that it ceases to have any relation to the One

The capitalization of "O" in "One" is both present in the source text and intentional. Much like the notion of capital "T" Truth, capital "O" "One" gestures at a noumenal, platonic, ineffable, singular One. Multiplicity tells us that rhizomes reject this unity.

Multiplicity in Film: Ex-Machina on Pollock

SPOILERS AHEAD

Ex-Machina is, in my opinion, the greatest film of all time. If you have not seen it, I highly recommend you stop whatever you are doing right now and watch it. It has everything: turing tests, meditations on Prometheus, existential crises, nature vs nurture, disco dancing, references to Wittgenstein. It's a psychological thriller that builds immense tension with Sorkin-esque dialogue between only four characters. It's framed and shot with an intentionality rivaled only by Wes Anderson. I could go on (and I will, in a separate post).

But today, we're here to talk about the Pollock scene, and how it relates to multiplicity.

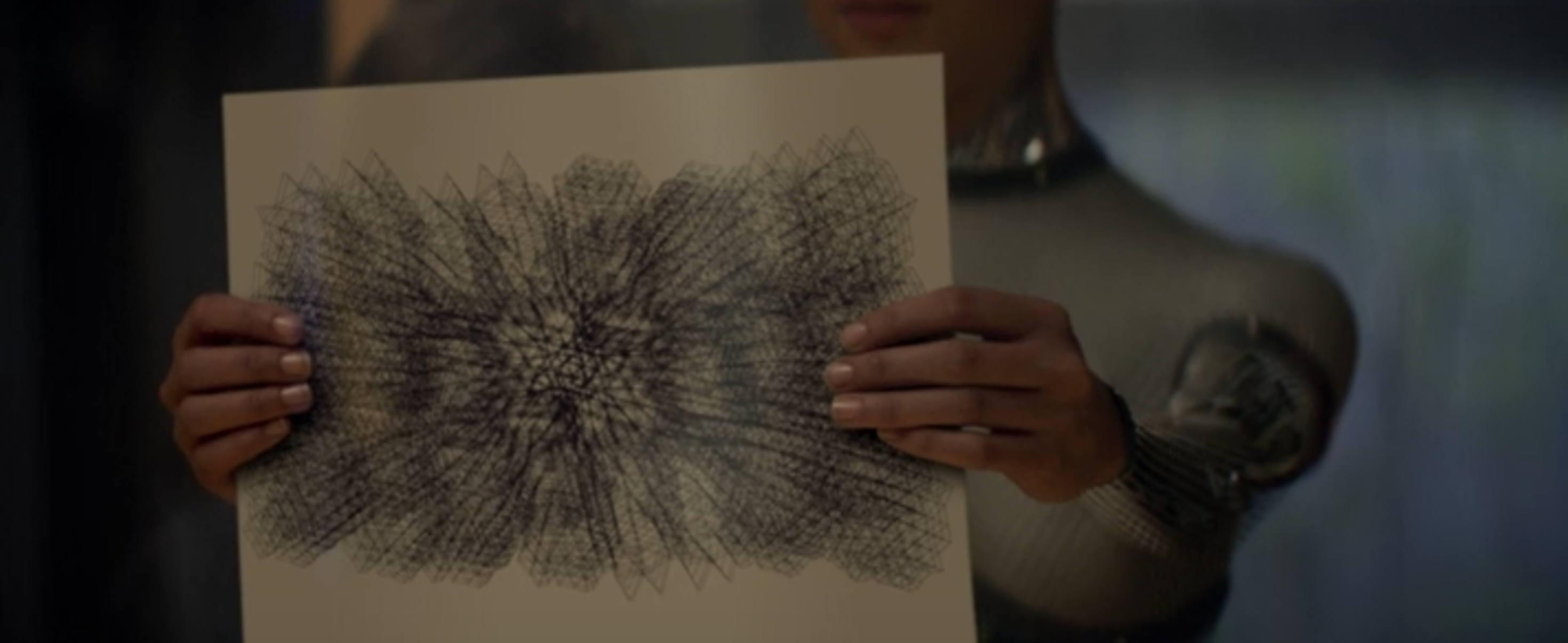

At the beginning of the film, embodied AI Ava shows her Turing tester Caleb an illustration:

Ava: What do you think?

Caleb: What's it a drawing of?

Ava: Don't you know?

Caleb: No?

Ava: I thought you would tell me.

Caleb: Don't you know?

Ava: I do drawings every day, but I don't know what they're of.

Later, Ava's creator Nathan shows Caleb the Pollock in his study.

Nathan: Jackson Pollock, the drip painter. He let his mind go blank and his hand go where it wanted. Not deliberate, not random, someplace in between. They called it automatic art... The challenge is not to act automatically. The challenge is to find an action that is not automatic.

Form the first dialogue, we know that Ava makes drawings every day, but does not know what they are of. We also know that she was expecting Caleb to tell her about her drawing. This hints that she is used to having someone interpret her drawings on a daily basis.

From the second dialogue, we know that Nathan is interested in finding an action that is not automatic. He also believes that Pollock's art has gone beyond the deliberate to "someplace in between."

Taken together, we can infer from these dialogues that part of Nathan's daily routine is to compare Ava's automatic art against Pollock's. As a multiplicity, the artworks form two different interpretations of the same cognitive process; namely, the ideomotor effect. In graph theoretic language, Nathan is comparing the link function that Ava implements with the link function that Pollock implements by comparing how they express the ideomotor effect. In doing so, Nathan hopes to learn something about what connections are being made in each of their respective cognitive processes.

At Nomic, we do something very similar when we compare the maps created by two different models.

Asignifying Rupture

Up to this point, we have been looking at rhizomes in a very static context (e.g. a particular connectome, a particular social network at a particular time, a particular piece of art). However, Deleuze and Guattari describe the rhizome as anything but static:

A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo

- ATP (25)

In this sense, we should not think of rhizomes as being limited to one particular thing. (Deleuze and Guattari reserve a different word, haecceity, to denote such particulars). Rhizomes are processes that constantly evolve, change, shift, and react. They are fluid and imperfect. Ava's picture in isolation is a haecceity. The dynamics of the Ava-Picture-Pollock-Nathan-cognition assemblage form a rhizome. As ATP puts it:

Principle of asignifying rupture: A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or new lines.

Language Models

As I mentioned in AI Trades Space for Time, the current wave of AI is driven by a paper titled Attention is All You Need. Attention is All You Need introduces the transformer architecture, which, as the title suggests, consists primarily of repeated applications of the self-attention operation: Letting denote a sequence of tokens, we can define self-attention as:

where q, k, and v denote feed forward neural networks with learnable parameters.

That looks very similar to the linear link function we saw earlier. In fact, we can interpret the entire attention operation as a link function; and where there is a link function, there is a rhizome.

But the transformer architecture is more than a single self-attention layer; it is a sequence of self attention layers. It implements a process that repeatedly constructs rhizomes just to break them down and build them again. Through this process of rupture and repair, deterritorialization and reterritorialization, the transformer is able to command language so eloquently that it's managed to convince at least a few people that it is conscious.

Russell, Wittgenstein, & Language

Both Bertrand Russell and his star pupil Ludwig Wittgenstein developed linguistic projects that were felled by asignifying ruptures.

For many years, Russell and Alfred North Whitehead worked together to formalize the set theoretic foundations of mathematics in their Principia Mathematica (PM). The PM aimed to construct a formal language that could be used as the basis of all future mathematics. Unfortunately, their project was proven to be impossible in 1931 when Kurt Godel published his first incompleteness theorem. Godel's key insight was that he could reinterpret the statements present in any formal language as statements about the boundaries of that language. Through this reinterpretation, Godel could simply read off statements that were outside the boundaries of a formal language from the definition of the formal language itself. In the language of ATP, Russell and Whitehead attempted to create One Mathematical-Rhizome, which Godel ruptured by reinterpreting the One as a multiplicity.

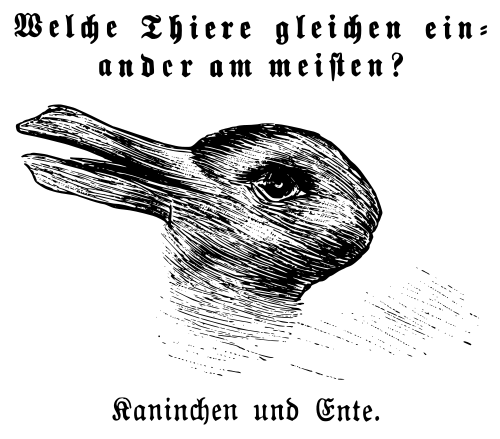

A similar story unfolded in the work of Russell's student, Wittgenstein. (ATP might call such a recurrence a refrain.) Wittgenstein, who is considered the greatest linguistic philosopher of the 20th century by many contemporary academics, has distinct early and late periods in his work. In his early work, Wittgenstein pursues a "picture theory of language," in which the construction of sentences paints a picture of the arrangement of facts present in the world.

As his thought matured, he increasingly realized that the subject of these "pictures of the world" was entirely dependent on the viewer of the picture. For this reason, Wittgenstein renounced his early work. He began interpreting language as a component of localized "language games," where game participants were only able to communicate meaning relative to the interpretive context provided by their shared way of life. The duck-rabbit illusion, which was made famous in Wittgenstein's posthumously published work Philosophical Investigations, illustrates the context sensitivity present in both pictures and language.

In the language of ATP, Wittgenstein realized that the existence of multiplicities ruptured the One World that his picture theory of language claimed to depict.

Hyperstitioneering

The emerging field of hyperstitioneering takes advantage of the flexibility that asignifying rupture allows in the language-culture-rhizome. A hyperstition is an idea that forms a positive feedback circuit with language and culture as components. A simple hyperstition is presented below:

You are now aware of your breathing

Through the interpretation of the language itself, a physical change (namely, your current awareness of your breathing) was manifested in the world, and the statement became true.

Hyperstitioneering concerns the engineering of hyperstitions. We have already seen an example of hyperstitioneering in this post - the injection of the word rhizome into the Nomic pitchbook profile. By advertising Nomic as a manufacturer of rhizomatic instruments, people will begin looking at Nomic to inform their understanding of what it means to manufacture a rhizomatic instrument. As this language proliferates throughout the internet, whatever it is that we are doing at Nomic will become increasingly looked at as the reference for what it means to manufacture rhizomatic instruments. In the limit, the statement "Nomic manufactures rhizomatic instruments" will become true because we proliferated it.

In this same vein, writer Donna Tartt accidentally sewed a hyperstition in her novel The Secret History. In the novel, a character named Bunny writes a disjointed essay that centers around the made up concept of metahemeralism. This lead fans of the novel to begin using metahemeralism in internet discourse, which in turn caused it to leak into the Bing retrieval dataset. Now, you can have conversations like this with Bing chat:

As Bing, other chatbots, and this blog post continue to proliferate the term metahemeralism across the internet, Bunny's essay will make increasingly more sense. In the limit, it might even be regarded as the canonical example of metahemeralism.

Cartography & Decalcomania

The final approximate characteristics of the rhizome are presented with uncharacteristic clarity in ATP:

Principle of Cartography & Decalcomaina: The rhizome is alltogether different, a map and not a tracing.

The difference between a map and a tracing is in their representational capacity: a map is necessarily a lossy reproduction of its territory, while a tracing is taken as an exact reproduction of its territory. We only need to look at Borges' famous short story On Exactitude in Science to understand why rhizomes must be maps. In the story, Borges describes a map of a kingdom so precise that it grew to the size of the empire itself. Deleuze and Guattari would consider such a map a tracing of the kingdom. A tracing is inherently useless, as it provides no new information relative to the territory itself. The tracing is also inherently static; the exactitude of its reproduction gives it no room to breathe, change, or evolve.

A rhizome, on the other hand, can evolve precisely because it has the flexibility of an imperfect reproduction.

In Summary

We have finally built up all six approximate characteristics of the rhizome:

- Connection: Any point on a rhizome can be connected to anything other.

- Heterogenety: Rhizomes ceaselessly establish connections, even between seemingly unrelated domains.

- Multiplicity: Rhizomes do not reproduce any One Truth. They are inherently multiple.

- Asignifying Rupture: Rhizomes are flexible and dynamic. They can break and reform while maintaining continuity.

- Cartography & Decalcomania: Rhizomes are maps and not tracings. Their imprecision is what enables them to evolve.

With this newfound knowledge, it will likely not surprise you that I consider this post a rhizome. It draws connections between several heterogeneous domains, and it will undoubtedly trigger a multiplicity of reactions that will rupture any connections that I tried to make.

It is imperfect, and it must be. It is not a tracing of the rhizome.

It is A Map of the Rhizome