A Vector Space Model of Management

Over the course of the last year, Nomic has grown from 3 people to 18 people. As an introverted engineer who's only ever managed an intern before, this forced me to learn a ton on the job (primarily by making mistakes). Perhaps the most impactful lesson I've learned concerns the relationship between employee direction and productivity. Since everything looks like a nail when you have a hammer, I've conceptualized this lesson through the lens of linear algebra.

Your Company is a Vector

Let's assume that we can parameterize all possible startups as vectors in a high dimensional vector space . At any given time, our company will be a vector in this space.

The magnitude of a company vector, , represents its execution speed. A large vector corresponds to a company that is moving quickly.

The angle of a company vector, , represents the direction it is building in. The role of CEO is to set the direction of the company, which directly corresponds to managing .

Your Employees are Vectors

The primary way that a CEO manages is by communicating their vision and tasking employees to accomplish company goals. If we view employees as tiny one person companies , they will be elements of , the same vector space our company vector lives in. It therefore feels reasonable to model the overall company as the sum of individual employee vectors.

The relationship between company direction and employee tasking is now clear; a CEO can directly modify the direction of the company through the tasks they assign to employees. However, there is a cost to exerting control over .

The Direction-Magnitude Tradeoff

Employees are people, and people are most productive when they are working on things that they enjoy. Unfortunately, startups often require people to work on things that they might not enjoy. When someone is working on something that they don't enjoy, they will naturally be less productive.

In our model, this manifests as a tradeoff between the magnitude and direction of employee vectors. The critical idea here is that as a CEO exerts more control over by tasking employees to do necessary but unenjoyable tasks, employee productivity will decrease. This results in a net decrease in the overall velocity of the company.

Intuitively this makes sense. When I was working as a machine learning engineer, I would regularly work on models over the weekend, but I would never work on our unit test suite over the weekend. One of the first major challenges I encountered when the team grew was tuning the tradeoff between and for each employee.

I've found two ways to adjust an employee's while minimizing the impact on . The first is to try, to the best of your ability, to shift what an employee wants to work on. This is primarily done by facilitating buy-in from the employee you want to impact. If the employee understands why what they are working on is important, and how it serves the mission of the company, they will be more amicable to working on it. This is why being a mission driven company is so critical. When a team is bought in on the mission, you don't have to keep recommunicating why the work is important; you simply need to communicate how their tasking serves the mission.

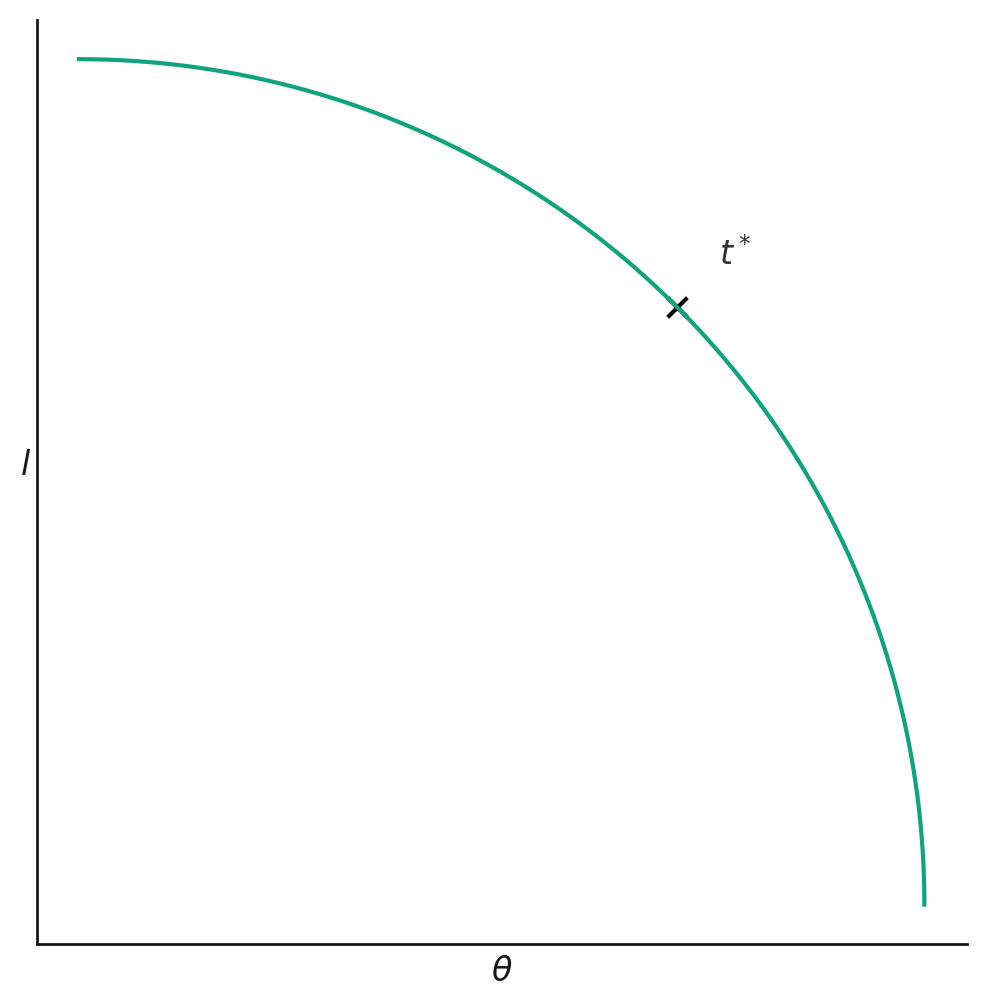

The second way to impact while minimizing the impact on is to leverage the nonlinearity of the direction-magnitude tradeoff. For most employee vectors, the relationship between direction and magnitude looks something like this:

The goal of a manager should be to achieve a position on this curve where they can maximally impact direction while minimally impacting magnitude. In the diagram above, I denote this point as , or the optimal tradeoff point.

Future Directions

I suspect that there are several interesting extensions of this model that will reveal themselves over time as I continue my management education by fire. A few particularly interesting directions might include:

- multi product companies as subspaces of company space

- modeling nonlinear employee interactions

- modeling employee burnout with dynamic